Introduction

This year I have been volunteering on Norfolk’s nesting beaches for little terns with the RSPB.

The RSPB aims to protect this sea bird species each season across the country to try to protect and boost population numbers. Their project has several other objectives you can find out about using the link, should you be interested.

This post is more about discussing and sharing my own experiences as a volunteer. I hope I can help you know if it may be something you are interested in trying yourself, or at least teach you a little more about sea bird protection in the UK.

As a volunteer, you can choose to help warden the beaching site as little or as often as you like. I tried to go at least once a week to see the development of the nesting sites and the birds progress from egg to fledgling, which was pretty rewarding!

If you want to get more involved than just wardening (keeping dogs and humans away from the site/educating on the birds) the team are also very willing to have volunteers help with data collection, which is something I really wanted to get involved with.

Where?

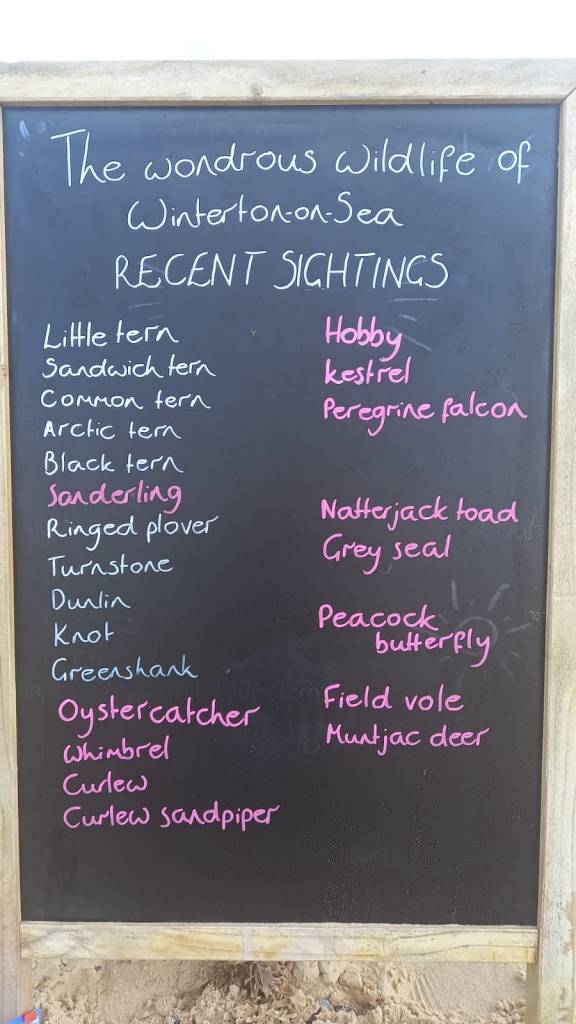

As mentioned, the project has many sites across the UK. However, in Norfolk, there are a couple of sites the RSPB volunteers focus on. These are Eccles and Winterton.

Nesting

Around May/June time the little terns start to arrive at our beaches, having migrated from West Africa for the nesting season.

Upon arrival, they pair up and eventually start making a small scrape (divot) in the sand upon which they intend to lay their eggs (usually between 1 and 3 eggs are laid).

Before all this, the RSPB and volunteers lay out a fencing structure, where they assume the birds will nest, in the hope of deterring all sorts of possible disturbances. Disturbances could be from humans, dogs or wildlife such as Muntjac deer or foxes that may wish to feast on eggs and chicks alike!

Once the nesting season begins volunteers and staff alike warden the beaches (almost 24/7 at peak) to prevent disturbances, mainly from humans/dogs. Scaring off predators from the air, such as the Kestrel’s and Hobby’s is another task, but one that is often less successful! They will also educate and interact with any members of the public who wish to learn more about these little visitors.

In addition, data collection also takes place to help the RSPB assess and monitor populations, with the hope that they find increasing numbers!

Nest histories, nest counts, clutch counts, predator disturbances, human disturbances, fledgling counts, diversionary feeding, ring-re-sighting and weather surveys are all carried out. This year this was done mainly by the new phone app (partly developed by myself) which makes collecting all this data very quick and easy!

This sounds like a lot when you first start but rest assured the team have the time and patience to go through the process for this data collection with you. It is also all explained within the data collection app, making it easy for you to feel like you’re really helping out with conservation efforts and collecting good, accurate data at the same time.

Adults constantly go out to see and catch small fish and sand eels to feed their young, so there is always some action to enjoy when visiting the beaches to volunteer. By becoming a volunteer you also obtain a license to photograph the birds which you wouldn’t be able to do otherwise, due to their protected status.

Issues

If you’re just starting out in conservation you may not yet know that problems and issues are common and often incredibly frustrating as there’s little you can do to stop mother nature in her tracks!

However, the first issue that arose was one caused by humans. Initially, we had marked the nests to colour code each one and record data for each nest. Unfortunately, it seemed an egg collector used these to their advantage and may have taken some eggs off the nest for their hobby. Although this wasn’t confirmed it is a known issue and this meant that the team no longer felt comfortable marking nests out. The result of this meant we could no longer record nest histories for individual nests and lost a lot of possible data collection in the process.

In addition to this, the nesting site at Eccles was deserted by the birds around a month in. I witnessed this first hand when a Hobby (British bird of prey) came across the nesting site and scared all of the nesting adults away from the beach. I sat there for a further hour or two without seeing the birds return and they never did! Kessingland, in nearby Suffolk, also suffered the same fate. Fortunately, the team believed the adults migrated down to Winterton as we had a huge number of nesting pairs there this season, over 300!

The predators, such as the Hobby, Kestrel and occasional Peregrine, were a nuisance all season. Despite lasers and horns to try and scare them off, as well as feeding platforms to try and deter them from our birds, our efforts were often unsuccessful. Multiple chicks (mainly by kestrels) and adults (mainly by hobbys) were predated this season.

Fledglings

Towards the end of July and early August the season starts to draw to an end. The young start to build up their strength and confidence as well as get their adult feathers through. This means they are ready to fly and ready for that big migration back to Africa!

As you can see from the images below we witnessed a huge number of successful fledglings leaving the Winterton beach this year! Despite the failings as Eccles and Kessingland it seemed to be a somewhat successful season overall as a result of the success here!

Image credit to RSPB Norfolk Little Tern Volunteers

The Team

If nothing else was gained from this experience, meeting a whole host of new people, passionate about wildlife conservation, was a certain positive. Tara, Alice, Lottie, Paul, William were all employed by the RSPB and were nothing but welcoming and willing to help with any given issue.

I seemed to spend the majority of my shifts with Tara and can honestly say she was extremely welcoming, as well as knowledgeable on UK wildlife and birds especially, making my experience all the better for it!

If you are looking to become a field officer, my understanding is that it is a 4/5 month contract and intense work. However, you will get a great deal of experience in both ecological monitoring and conservation, as well as community engagement. Both of which are valuable skills for anyone looking to build a career in the conservation world!

I also met a number of other volunteers, including Lauren, Helen, Richard, Susan, and Lyn, all of whom shared similar passions and interests to mine. Many had volunteered previous years and it was great to be able to learn off of not only RSPB staff but also experienced volunteers.

Overall Thoughts and Feelings

This was a great experience for me personally. The ability to fit in volunteering around my busy schedule was a real plus. Furthermore, it was on an internationally recognised project, with an internationally renowned organisation, which was invaluable.

It really helped me personally, not only by giving me some experience on my CV but also to satisfy my desire to get out and help with wildlife conservation, after being stuck at home for 18 months from the pandemic.

I felt like I made a real difference in helping with protection and data collection, met some great people and had a good time doing it! The RSPB also offer compensation for driving costs to the site, so it was a truly cost-free volunteering opportunity.

If you would like to find out more about volunteering be sure to email norfolklittleterns@rspb.org.uk

One thought on “Protecting the Little Terns – RSPB – 2021”