Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS) are those animals or plants that have the ability to spread and cause damage to an environment in areas they don’t belong, that being areas of the world where they don’t naturally occur. This damage can be in the form of that to our environment, economy or health.

For example, one of the most famous and well-known INNS is the Lionfish of the Caribbean. These fish come from the Indian Ocean, yet they have found their way to the Caribbean and are destroying the local ecosystem. This is because here they have no natural predators while eating anything they can fit in their mouths!

The lionfish is just one of the better-known global examples, but did you know one of our most beloved creatures at home is actually also a non-native? Although the star of the Beatrix Potter novels, Peter Rabbitt’s home isn’t truly the rolling British countryside.

The common rabbit was in fact originally native to the more southern European and northern African countries before it was transported over to the UK in colonial times. In fact, only the mountain hare of all our bunny-like friends is native to the UK, with the brown hare also an introduced species.

In general, the marine INNS are the ones less talked about, discussed, or to be honest understood in terms of their impact and range.

So let’s look at marine INNS in the UK, what the problem is, where they came from and how we might stop them!

What is the Issue?

As already suggested introducing a species that is not meant to live in a certain area can negatively impact the natural balance, as seen with the lionfish example.

You may think that an animal transported to live in an area where it isn’t supposed to be may struggle, due to the differing climates, predators and food sources available to what they are adapted to – but sometimes they thrive!

INNS are the “main driver of biodiversity loss across the globe” and “cost our economy hundreds of billions of dollars each year” according to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

By out-competing natural species for resources, invasives can become dominant and displace native species which decreases overall biodiversity, in turn reducing an ecosystem’s resilience and ability to deal with other pressures it may face, such as climate change. They can also cause a loss of genetic diversity and introduce pathogens (disease-causing bacteria) into native populations.

INNS can also impact other organisms when one species affects another via another species. For example, where there is a shared natural enemy or a shared resource, INNS can compete or change the dynamics within these finely balanced ecosystems.

Predicting or even noticing these chain reactions occurring is incredibly difficult, while the impact of multiple invasive species at once can have large and complex impacts on an ecosystem. This makes these scenarios extremely difficult to monitor and control, especially in the marine environment which is relatively difficult to see and access in comparison to conducting land-based studies.

In terms of direct impact on ourselves, a reduction in species variety can also directly remove valuable species for humans, such as our main food species.

Moreover, INNS can directly affect human health, as infectious diseases are often imported via INNS, through moving travellers, birds, rodents and insects.

Total annual costs, including losses to crops, pastures and forests, as well as environmental damages and control costs, are likely to be nearly one trillion dollars per year. This does not include a valuation of species extinctions, losses in biodiversity, ecosystem services and aesthetic value as these are difficult to quantify.

These economic costs can be incurred by different industry sectors including commercial shipping, recreational boat users and offshore industry due to increased fouling (when organisms attach themselves to underwater objects like boats, rope, pipes and building structures – causing more maintenance costs) and also to aquaculture industries due to the potential increased competition for resources, diseases and predation.

Marine Hull Fouling Whitby 37 – Credit GBNNSS with thanks to parkol marine engineering ltd

Examples of Problem Marine INNS in the UK

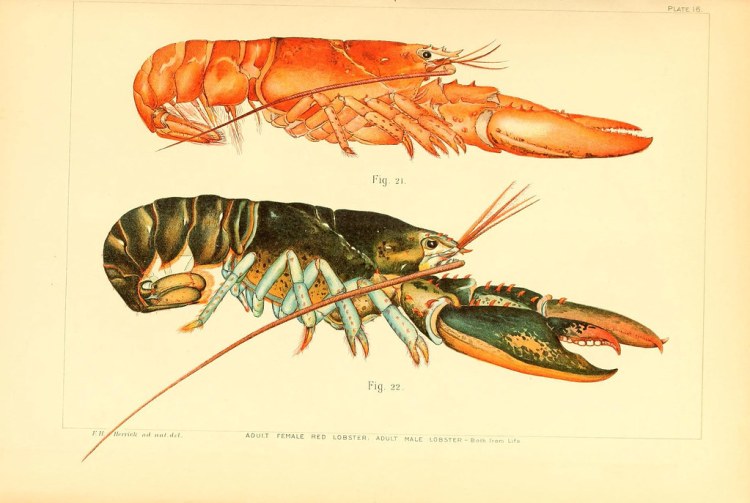

American lobster

American lobsters are more aggressive and larger than our native European lobsters, so can outcompete the native population. This added competition for resources is also a threat to other environmentally and economically important species such as native brown crabs.

Chinese mitten crab

Predation and competition are likely to reduce native, benthic (bottom-dwelling) invertebrate populations in freshwater and marine systems.

It also carries a number of diseases, including tremor disease and black gill syndrome. It can also host Oriental lung fluke, which may affect humans.

Darwin’s barnacle

Appears to have entirely displaced native barnacle species in some places, including Lough Hine and the Tamar estuary. This is also a species notorious for fouling vessels and equipment and interfering with mariculture (marine organism farming) activities.

This can lead to increased fuel costs for heavily fouled ships, as more fuel is required to maintain a heavier ship. Costs will increase for cleaning and maintenance for both the shipping and mariculture industry, while the latter can also experience stock loss.

Slipper limpet

This limpet can smoother surfaces by stacking and spreading rapidly. This prevents native seabed species from settling and through the deposition of faeces and sediments hard-surface habitat availability is reduced. This loss of habitat will diminish the population of important mussels and oyster fisheries in the UK.

These fisheries are likely to incur further economic costs due to the need to clean shells fouled with slipper limpets and sort and gather heavily infested catches.

How do they get here?

Increasing travel, trade, and tourism associated with globalization )increased global connections between countries) and the growing human population have facilitated the intentional and unintentional movement of marine species.

Marine non-native species are introduced and spread mainly via:

- shipping ballast water (water taken and released at different ports to weigh down boats at the correct water level) and hull fouling,

- recreational boating via hull fouling,

- aquaculture via contamination of moved/imported stock and,

- natural dispersal.

What can be done?

There are many international and regional binding agreements and voluntary guidelines that include regulations on invasive species. Prevention requires collaboration among governments, economic sectors and non-governmental and international organizations.

There is a GB INNS framework strategy in place which take the general approach of identifying – reacting – containing. In the marine environment, the first step of identification/prevention through improved biosecurity best practice is key. Preventing international movement of INNS and rapid detection at borders are less costly and more effective than control and eradication.

However, as you can imagine this prevention and containment of INNS is incredibly challenging, especially when dealing with small and hard-to-monitor species such as sea squirts, algae and limpets across the vastness that is the marine world.

Management measures such as inspections of international shipments, customs checks and proper quarantine regulations are carried out in the UK. Ships are tested and decontaminated in UK shipping ports in an attempt to prevent ballast water contamination and hull fouling spreading INNS.

Current Work

As you now know, non-native species can become invasive, altering local ecology and out-competing native species.

However, there is currently a lack of evidence in the UK on the true impacts on protected areas and their important ecological features. Some species are better known than others, with those lacking data the ones harder to monitor, either due to their recent induction, identification difficulties, the environment they live in or just the size of the creature.

The interactions between invasive species and specific protected sites need further monitoring in the future to fully understand the impacts of certain species on features of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)(Natural England).

However, in order to combat these gaps in understanding organisations, companies, Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and charities are working to better understand the impact of INNS on UK waters, both on land and at sea.

For example, a Natural England & Natural Resources Wales study was recently undertaken in 2016 to study those lesser-known INNS and their potential impacts on the UK conservation of protected sites and species.

Eight species were selected due to the relevant lack of evidence and understanding of their impacts, these were: Asian kelp, Trumpet tube worm, Orange ripple bryozoan, Wire weed, Asian shore crab, Leathery sea squirt, Orange-tipped sea squirt, Devil’s tongue weed.

The study concluded that all eight INNS were found in one or more MPAs throughout England and Wales. However, actual observed changes in MPA features were only reported for three; Asian kelp, Wire weed, and Orange-tipped sea squirt, whose introduction had led to changes in ecological community compositions.

This shows that these lesser-known INNS need to be monitored to understand their impacts at the site level in the UK.

More work continues, not just in the UK, but globally to understand INNS and their impact on marine environments.

Want to Find out More?

- The most up-to-date source of information and identification of INNS is the Non-Native Species Information Portal on the Non-Native Species Secretariat website. This includes risk assessments for different species.

- The Marine Biological Association have produced a useful quick identification guide that can be printed out

Disclaimer: All views put forward in my blogs are my own opinion and not in any way linked to Organisations or Companies I have, or currently work for.

That was a lovely blog post young man

LikeLike